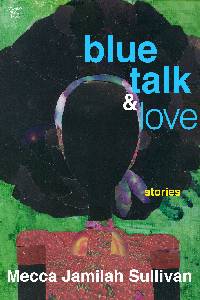

The award-wining collection Blue Talk and Love tells the stories of girls and women of color navigating the moods and mazes of urban daily life. Set in various enclaves of New York City — including the middle-class Hamilton Heights section of Harlem, the black queer social world of the West Village, the Spanish-speaking borderland between Harlem and Washington Heights, and historic Tin Pan Alley — the collection uses magic realism, historical fiction, satire and more to highlight young black women's inner lives.

The storylines range widely: a big-bodied teenage girl from Harlem discovers her sexuality in the midst of racial tensions at her Upper East Side school; four young women from Newark, New Jersey, are charged with assaulting the man who threatens to rape them; a pair of conjoined black female twins born into slavery, make their fame as stage performers in the Big City. In each story, the characters push past what is expected of them, learning to celebrate their voices and their lives.

In honor of Mecca Sullivan’s being named the recipient of the 2018 Judith A. Markowitz Lambda Award as an emerging LGBTQ writer, Riverdale Avenue Books has released a second edition of her acclaimed collection for which the Lambda judges called Sullivan, "An essential writer of our present moment.”

"We are so proud of Mecca for receiving this prestigious award. She made her fiction debut with Riverdale Avenue Books five years ago, when we were both new to the literary scene, and we are publishing an updated second edition with the wonderful quote from Ntozake Shange on the cover to commemorate this achievement,” said Publisher Lori Perkins.

******

“In Blue Talk and Love... the lives of wounded and glorious young gay women of color are portrayed with the delicacy of a mother tending to her terrible wounds…Sullivan enriches our lives with ...characters, who are so rich and impoverished at once.” —Ntozake Shange, author of for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf

"An essential writer of our present moment" —Judges for the 2018 Judith A. Markowitz Lambda Emerging LGBTQ Writer Award

Blue Talk and Love’s "voice, despite material that seems frankly contemporary, is paradoxically lyrical, nearly Faulknerian." —Rick Moody, judge for the American Short Fiction Short Story Contest

“Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s debut story collection is a remarkable work best described as elegiac blues… Blue Talk and Love stuns with subtle imagery, powerful linguistic energy, and chiseled, innovative control.” — LaShonda Katrice Barnett, author of Jam on the Vine

"Sullivan’s prose shocks, intrigues, and transports us through fourteen artful and unique stories. And so do her rich and inimitable characters, most of them young black women struggling in a world they did not make but one they must confront, tear down, and remake. Black girls matter and Sullivan shows us just how much." — Cheryl Clarke, author of Narratives: Poems in the Tradition of Black Women

From "Saturday"

Ms. Adelaide, the meeting leader added “PIE” to the list of trouble foods, which had grown to cover the entire page, leaving only a tiny strip of space between “SALMON CAKES” and “PLANTAIN CHIPS” for the three letters of the Clondon women’s apparent trigger. Malaya wished to liquefy and slide from her seat, find herself gone from the basement into that word, PIE, curled into the lower nook of the E as though it were a shaded ground below an apple tree. She wished for spots of sun to heat her sandaled feet as the leaves of her E tree rustled, and for the cool of an afternoon to raise goose bumps along her long, lean legs. In truth, Malaya was not so compelled by pie. She would eat the filling because it was there, and because it would be one of very few chances she’d have all week to indulge herself in plain view, right beside her mother.

What her mother did not know, what could not be written on Ms. Adelaide’s board for lack of space and language, was that Malaya would have preferred an endless plate of potatoes over pie, without question. Mashed, salted, swaddled in gravy or butter or both and served in a bottomless mixing bowl—that was how Malaya wanted to eat. And by now, at eight years old, Malaya had noticed in herself a tendency to choose quantity over quality—pools and pools of potatoes over a shared slice of fancy pie. She had not yet learned words like abundance or profusion or glut; the only word she could find to describe her trigger was MORE. Of all the women in the room—thirty at least—only two seemed to share her passion: the loud woman who had broken the ice what now seemed like ages ago, and a smaller woman beside her mother, who raised a hand only inches above her shoulder and said quietly, “I have trouble with plain white rice.”