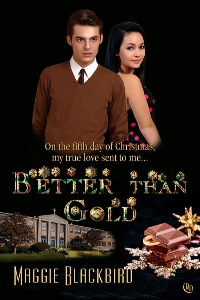

Sometimes chocolate is better than a golden ring.

Etta Bannon must endure another Christmas at the Indian Residential School for girls. With her heart heavy for home that is a two-day train ride away, all she has is the stolen moments with her beau to look forward to, but even the boy she cares deeply about cannot erase her longing for her family.

Charlie Shawanda is also stuck at the Indian Residential School for boys. Only a mere jog away from Etta, he longs to make their last Christmas at the school special before they graduate in the spring and go their separate ways. But what he truly years for is to call Etta his very own.

When a golden opportunity arises for Charlie to show his love, he must make a tough decision–endure the cruel punishment of the strap or miss out on a chance to tell Etta how he truly feels and maybe lose her forever.

December 1955

Spanish, Northern Ontario

It didn’t matter Etta’s clothes were donated. What mattered was that the double-breasted, wool jacket with the big shiny buttons Sister Maria had given her this morning fit closely around her breasts, accentuated her tiny waist, and swathed her pencil skirt that snuggly fit her hips.

For sure her new coat would earn her a long lingering look from Charlie at tonight’s choir practice once the afternoon chores were complete. Nor did it matter her annoying school number of forty-six was written in the lining.

If Sister Maria saw Etta at this moment, the old nun’s thin lips would pucker into her familiar wrinkled frown, because vanity was a sin. Maybe the so-called evil of self-admiration was why there was only one mirror in the school the students could use, and it spanned the six rows of sinks in the bathroom.

“Quit dallying. We got to go.” Bernice stuck her head inside. She thrust out the heavy gray smock.

Etta bent at the waist and removed the boots with the faux fur trim. If she was at home, Mom would’ve sewn rabbit fur around her ankles as she always had done when Dad returned with his haul from the trapline, the very place where Etta had been born. “I was trying on my new clothes. I’m wearing them to choir practice.”

“Sister Maria’s waiting.” Fear and urgency saturated Bernice’s high-pitched warning. “Move. Move. I don’t want the strap.”

The horrible five-letter word spread gooseflesh and a chill across Etta’s skin. “I’m hurrying.”

“You still got to hang your belongings.” Bernice tugged on Etta’s hand.

They dashed for the dormitory across the way, where the many cast-iron beds set up in two long rows were located.

Once Etta hung her coat and set her boots in the tiny closet assigned to her, where her two remaining skirts and blouses hung, she quickly put on the smock and her saddle shoes. Together, they darted for the stairs.

As they scurried to the basement, they passed other girls knee-deep in chores. Some swept. Others mopped. A few dusted.

Skeleton students, Sister Maria had referred to the girls who remained behind for the Christmas holidays, since their parents were unable to pay the bus or train fare to send them home.

Home. So far away.

A teardrop threatened to slide from Etta’s eye, and lonesomeness gripped her heart. Again, she wouldn’t get to see her family during the special day. Mom, Dad, and her younger brothers and sisters would celebrate by eating the deer Dad always hunted for them.

Etta and Beatrice reached the laundry room, where gray bags full of dirty clothes from the boys’ school yards away waited for them. The stale smell of must lingered under Etta’s nose. She reached for the first bag and dumped a pile of pants onto the wooden table used for sorting.

“Were you checking yourself out for Charlie?” Beatrice giggled. She pushed at her cat’s eye glasses that forever slipped down her beak-like nose.

Since they were safely tucked away from the prying ears of the apostolic sisters, Etta also let the giggle in her throat burst free at the mention of Charlie’s name, as it always did, even when the awful lonesomeness clung to her heart like the icicles hanging from the eavestrough of the three-story brick school. “What do you think?”

“He’s the finest there is.” A trace of wistfulness lingered in Beatrice’s words.

Etta began rifling through the pants pockets. Maybe a boy had left Beatrice a note. It’d be a great surprise and something to make her best friend smile. Beatrice was too kind and sweet to go unnoticed. But the two notes Etta unearthed were for the other girls, which she quickly stuffed into the pouch of her smock to hand to them afterward.

When she came to Charlie’s pants, her shriveled heart puffed back to its normal shape. If only they could see each other, instead of hiding what they shared. But getting too close to a boy was a sin, according to Sister Maria, something Etta turned her nose up at. Mom had told her she could hold hands and kiss.

She dug inside the front pocket. Her fingers touched a slip of paper. Quickly, she peeled out the note and opened it. Charlie’s perfect penmanship the priests demanded—and the same for the sisters—popped off the paper.