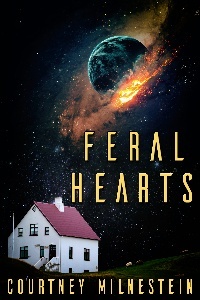

There is a story about Maiden’s Point, an old story, a story about a jilted lover who, in her grief, threw herself into the sea.

It is the warm summer of 1993, and across Gloriana, Super Soakers are all the rage, children wear Ray-Ban sunglasses and Airwalk skate shoes, and there is not a boy alive who is worried about the mention of a new planet glimpsed just within the shadow of Pluto. No boy save for Dorin, on the cusp of adolescence.

Having recently moved from the city to a large communal home in the country, Dorin has to adjust to his new life in the country within a house his father constantly assures him is haunted. He tries to balance his budding friendship with Ailbe, a boy from one of the other families at the house, with the growing shadow of the tenth planet Nimue as, all around him, it feels as if the adults he has trusted for so long seem to be making increasingly irrational decisions.

I didn’t have a clear plan that morning; all I knew was that I was content to pass on the prospect of an awkward breakfast in which my parents would attempt to convince other people their age, other children my age, that I was the sort of child they should make time for, the sort of child who brushed his teeth before bed, who always came in from playing in the street when he was called, who never spoke back to his parents. No, I was a different kind of boy, a wild animal who could not be tamed by the need to belong that my parents felt so very, very keenly.

That was how I happened to be in the bell tower, looking out over those same dark waters that the maiden of Maiden’s Point had once looked out over; that was how I first met Ailbe.

A head shorter than me, his hair so blond it was white, one minute I was alone, and the next he was there, standing on the other side of the large brass bell that all but not quite filled the tower, slipping around the side of the bell every time I stepped towards him, ensuring that he remained forever obscured throughout that first fateful meeting.

He was a rare animal, something fragile and dangerous, glimpsed only in his movements in opposition to me.

“Who are you?” he called out, his voice full of anxiety, a faint accent, something suggestive of Ablach, rich and lyrical.

He was a pair of bare legs and white Converse on the other side of the dull brass, a ghost amongst the rafters of that high tower.

I felt the wind stir behind me, the whisper of the dark ocean.

“Dorin,” I said, and then blushed at the stupidity of my response, for how was he to know who I was.

“Who’s Dorin?” the voice from behind the bell demanded.

I shrugged.

“Me. I’m Dorin.”

Slowly, cautiously, like a frightened animal emerging into some forest glade, Ailbe stepped forth, his fringe in his eyes, an oversized T-shirt obviously inherited from an older sibling draped about his small frame, a smiley face in yellow with crosses for eyes and its tongue sticking out.

Being confronted with him then, in that moment, on that early morning, was a relief. Clearly the runt of the litter, there was something fragile and unlovable about Ailbe, that same thing that made you angry when you saw stray dogs, and made you want to kick them. In those days, perhaps dogs were less aggressive, and there weren’t so many of them running wild, so this may be hard for you to imagine.

“And who are you?” I asked, instantly feeling at ease due to the general state of him, by his underfed, animal shape, his almost white hair, his furtive uncertainty. There was something about him that made me think of those strays that had learnt to live in the great emptiness but have never quite forgotten that once they had been loved.

With sudden vividness, I recalled the dog that my uncle had owned back in Lusatia, and I remember the story of its boisterousness, its excitement, and how one day it had escaped into the fields behind my aunt and uncle’s house and never returned, and how everyone had told me that it bad probably gone to live with someone else, but I knew in my heart that it had died alone.

“My name’s Ailbe,” the boy in the oversized T-shirt said, his lilting voice cutting through my thoughts.

I looked up, confused, uncertain as to why he was telling me this, and then remembered that we have never met, and he, this frightened, bare legged animal, was attempting to introduce himself to me, to make friends with me, though from his general nervousness, you never would have guessed.

I nodded, trying to take all this in my stride.

“What’s up, Ailbe?” I said.

He shrugged.

“I don’t know.”

And smiled.

“The sky.”