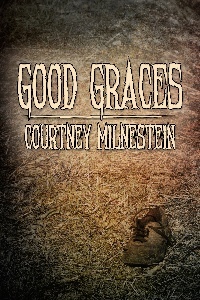

What makes your perfect forever home slightly less than perfect and a lot less than forever? Having the ghost of a young boy haunt its halls, perhaps?

After considerable scrimping and saving, John and Terry have finally put down their first mortgage payment for their new home in St John’s Wood in leafy North London. This, John believes, is their reward, their payment for all the long, hard years of enduring shoddy flats and sketchy landlords; this is what they deserve. Yet during the renovations of their kitchen, when a mystery shoe is found in an old fireplace and a lonesome ghost begins to make an appearance, they find their relationship tested not just by the haunting, but by the strange ghostbuster who arrives on their doorstep unannounced.

John frets and worries, but will they be able to put the matter to rest once more and for all? Will the spirit of their dead visitor find a way to move on, or will the dream of actually owning property in North London become a nightmare?

When he awoke, he found himself caught between Terry’s arm and the tangle of the sheets, his chest damp with sweat, the tangled dark mass of his hair plastered against his forehead. Gently divorcing himself from Terry’s embrace, he lifted himself from the bed into which they had fallen, gathering up a pair of boxer shorts and a T-shirt, not especially concerned with who had initially worn them, and made his way out of the bedroom, pulling the door softly closed behind him so as not to disturb his peacefully slumbering boyfriend.

It would have been easy to stay where he had been, wrapped up in the heat of the late summer and Terry’s touch, and yet a slow restless wakefulness had dawned upon him, and even though he had tried to fight it, his eyes closed in the dim evening of the shadowy bedroom, he was soon decidedly awake and left with no retreat back into sleep.

Standing barefoot in the chaos of the kitchen, waiting by the kettle as it slowly, agonisingly took its time to boil, he looked at the walls freshly peeled off paper and plaster, the marker pen etchings of previous occupants, the instructions left by electricians to those who would follow, marking out technical details of the kind that he himself had never really bothered to learn or understand.

Leave that for the manly men, he thought dismissively, looking down at his hands, as if instinctively inspecting them for signs that they might have betrayed him, that secretly, whilst he slept, they might have been up to something of the sort that he typically associated with the occupations of his father, his brother, things that he felt were beneath him.

“Oh, you’re a big tart, John,” he admonished himself, speaking in the playful way in which forgotten best friends had addressed him.

It was true, he wasn’t embarrassed about it. He knew what they said, that familiar caricature of men who were too effeminate, too girly, given to preening, speaking with lisps, and so what if he saw himself in this cruel portrayal; vacuous he might have been, womanly he might have been, but at least he was happy.

“And you are, aren’t you?” he said to himself, finishing the inspection of his nails, turning his attention to the floor. “You are happy, aren’t you, John?”

In the end, they were finally in their forever home, weren’t they? In the end, the house was their own. If only he hadn’t noticed that bloody shoe in that bloody stopped up fireplace.

At his back, the kettle whistled, a shrill siren song drawing his attention back to it. He lifted his head from where he had been studying his bare feet, the tufts of hair on each of his large toes, the dirt and grit that was uncomfortable to walk on, reminders of the fact that the builders had not returned.

When he looked up, it was then that he saw the figure of the child, standing before the fireplace, warm complexion and loose shorts, a baggy T-shirt that slipped down to reveal the jagged edge of a collarbone, a pale blue T-shirt with a faded cartoon character, a mouse, John thought, Martin Strauss Mousk, he later recalled, remembering the character from an annual his aunt had brought him as a child.

Irrationally, his first instinct was to scream, but then his adult brain kicked in, rationality and responsibility taking over in a situation that could have swiftly escalated into drama.

“Hello, you,” he said, slightly self-conscious of the fact that he was standing amidst the ruined kitchen solely in boxer shorts and a shirt, “don’t you know it’s rude to just wander into people’s houses uninvited?”

Had they left the front door open, he thought, and made a mental note to chastise the builders when they arrived tomorrow. Imagine if someone had caught him and Terry in the throes of passion. A blush filled his cheeks, a warmth stirring in his belly as he remembered their lovemaking and was instantly transported back into the moment, the younger man’s gentle kisses on the nape of his neck.

Inappropriate, John, he told himself. There was, after all, a child present.

The child in question said nothing, standing sullenly before the fireplace, looking weirdly out of place, incongruous with his surroundings. He must have been twelve years old, John thought, and sadly he remembered that this was the age at which Terry’s cousin had died. Dirty blond hair, knees covered in marks as if he’d been crawling on his hands knees. His eyes travelled the length of the child, and he found himself staring at his feet, one leather shoe on the left foot, the other naked, bare.

A chill of recognition stirred along the stations of his spine.

“Oh Jesus,” he murmured.

When he looked up again, the child was no longer there.

Behind him, the kettle continued its song.