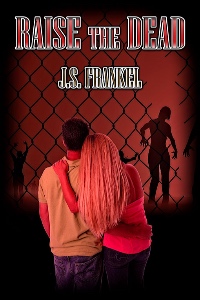

Raising the dead would be considered a miracle by anyone. In the case of a lone test subject, it’s anything but. The nameless carrier is, in fact, a walking plague that wreaks evil upon society. In a battle for survival, only Harmon Hapwell and Britt Besch, high school students, can stop him.

Newton Town, Lincoln County, Oregon, downtown area, June second, present day. Sunday, eight-forty-five AM. Ten days before summer vacation.

The crowd milled around Warbler’s Department Store, waiting for the doors to open. It was an Everything-Twenty-Percent-Off-Day, and those who lived to shop and who had the funds wanted to slake their buying thirst.

Everyone except me, that is. I had exactly seven dollars in my pocket, a recent acquisition from my mother, who’d obviously pitied my lack of funds. As a student, I had no part-time job to tide me over. Newton Town thrived on tourism, as it sat right next to a mountain range that offered camping, plus a spectacular scenic view of the mountains beyond. It also had numerous bike trails, and summer bike riders loved going there.

And, in a specially sealed-off-by-yellow-tape area located near Warbler’s, we had a hole dug out of the earth that would soon house a time capsule. Anyone and everyone could contribute to it. It was large enough to hold at least three people, but our mayor promised that only non-human items would be placed inside.

I’d pitched in with a few books. Other people had donated pictures, toys, DVDs, and various and sundry items. A single cable attached to a crane held it aloft, and it dangled over a six-foot wide hole that was fifty feet down. That depth was actually too deep. The workmen had made a mistake, but no one had bothered filling in the hole, so everyone left it alone.

Signs saying Keep Out—This Means You made people laugh, but no one was interested in stealing anything from the capsule. It would be buried next year, and all the neighboring counties plus the major newspapers would show up for the ceremony—or so they promised.

However, time capsules and touristy things notwithstanding, numbers were everything. Times were tough. No one was hiring, not even at the local ice cream shops, and wasn’t that just too bad? Rhetorical—it sucked, but everyone was in the same boat.

Not having a part-time job bothered me. Financially, my mother and I were hurting. She was single, widowed, and not looking to remarry, as she didn’t want to go through the heartbreak of losing another husband, or so she said.

We’d moved here from Chicago about a year ago. Prices were cheaper, and my mother had a decent office job. Still, we had to pay the mortgage on our house and buy food, and that left precious little money for luxuries.

Luxuries were things that many other kids took for granted. No smartphone for me. I had a used computer, a ton of old books that I’d scored from online library sales and paid for by my mother—I paid her back by doing all the cleaning and washing chores—and a number of computer software games. That was all I needed. My mother’s take-home pay wasn’t great. In fact, it was just enough for both of us, so I got used to having less.

If I had one wish, it was for a new name. Harmon didn’t sound tough, at least, to me. As for my family name—Hapwell—that also sounded sort of lame. Growing up, people either called me Harmless or Hapless or Hopeless.

Getting insulted on a daily basis could really scar anyone’s psyche, and on more than one occasion, as a little kid, I’d come home crying. Chicagoans weren’t noted for being sensitive. They were tough-minded people, and the kids there were no exception. A person could only ignore insults for so long.

However, my mother, short, slender, and just as tough-minded as everyone else, raised me to be self-reliant. “Your father would’ve wanted it that way,” she’d said. “You have a name to be proud of, and you should never let anyone tear you down because of who you are or what your name is. Ever.”

Call it a cliché, but it was easy for her to say that. She had a nice, normal name—Anna. She didn’t have to worry about people making fun of her. As for my father, I never knew him. He’d died when I was a baby.

All I knew was the picture of him on our mantelpiece at home. Short and stocky, he had a narrow face, blue eyes, and blond hair. Small ears, thin lips. I looked just like him and was built just like him—on the short side of five-eight—except that my hair was dark, as were my eyes.

In short, I looked very average, or, to be honest, slightly less so. The kids at school knew that, and growing up, I was on the pudgy side. I got teased a lot not only for my name but also for my physique—or lack of one—but after my mother had that heart-to-heart talk with me, something resonated. I had to rely on myself, so I went on a diet and learned how to fight. I didn’t pick fights, but if someone insulted me over my name or looks, then it was on.

Yes, it was childish, but kids my age never thought about the consequences until it was too late. And because they didn’t think ahead, they said and did things that they regretted later. During that time in my life, their stupidity and my willingness to mix it up taught me how to brawl.

My mother became an expert in applying bandages and iodine, and she got very creative with it. I copied her style, and while I looked like a mummy, eventually, I got the hang of it, healed up, and then got into another scrape where I had to tape myself up all over again.