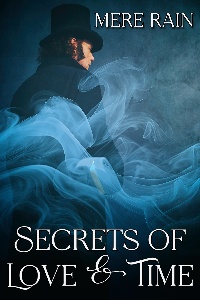

The detective's faithful assistant has been keeping a secret from him. No, not what you're thinking. All right, make that two secrets.

Love between men is a serious crime in Victorian England, but that's not why Micah Sheer is concealing his feelings for private detective Leander Maine. Sheer has a supernatural secret, that would endanger not only the two of them but thousands of other lives. Maine has devoted his life to uncovering truths -- and Sheer has spent years leading him away from them.

Leander Maine is a keen observer, and he can't help deducing that his assistant is hiding something from him. Compelled to discover his friend's secret, he begins following Sheer, and soon the certainties of the reality he has always known begin to crumble beneath his feet. But Sheer's motivation is still hidden from him, and Maine cannot imagine what could justify his deception. What truth could be important enough to risk their friendship? And what price will they both pay if the truth is uncovered?

These considerations passed through Maine’s mind in a moment and scarcely showed in his expression.

“Never mind, Sheer,” he said. “I don’t mean to berate you. Either the fellow will turn up again, or he won’t. I will add him to my not-inconsiderable list of enemies to watch for.”

And you, Sheer, he thought, heart aching. I will watch you as well.

He had trusted Sheer absolutely. Not the infallibility of his judgement or the incisiveness of his mental acuity, but his good will, his fidelity, yes, those Maine had trusted as he had trusted no one else in all his life.

He had thought Sheer trusted him as well. Perhaps he did; he made no effort at evasion or concealment when he left their rooms. Maine had no difficulty following him.

The first time Sheer walked to Cumberland Market. There he bought a yellow apple from an old woman with a concealing shawl over her head, speaking with her for several minutes. As Maine had known Sheer to engage in idle conversation with all sorts of persons, this was only suspicious in that there were many closer markets and grocers from which an apple could have been obtained. When Maine returned to the market after ascertaining that Sheer went nowhere else but home, the old woman and her cart were gone. The adjacent costermongers denied having noticed her at all.

The second time he followed Sheer to a pub, where he remained for about half an hour. When he came out a young man trailed after him, stopping him with a hand on his arm. Sheer smiled and shook his head, but the youth stepped closer, putting the other hand on Sheer’s chest. Maine felt his heart thump strangely, fast and uneven and painful. Sheer shook his head again, removed the other man’s hand, and strode away, leaving the young man gazing after him in disappointment.

The third occasion did not occur for another week. A new investigation had presented itself, or rather been presented by Maine’s acquaintance Worley, a journalist who passed along items of mystery, interest, or confoundment in exchange for the occasional story that might be related without harm to Maine’s clients’ interests. A small child had gone missing from a hayloft. Her father and uncles had been working in the barn below, accompanied by two sheepdogs who would certainly have given the alarm had a stranger entered. At first the girl was assumed to have slipped off in search of a playmate or other harmless activity, but she did not return and the search party found no trace of her. The dogs whined, unable to find the scent.

Maine and Sheer had spent two days in the countryside, making inquiries. No tramps, travelers, tinkers, gypsies, circuses or other suspicious types had been brought to light. The girl’s mother wept over her iron cookpot and her father’s face was aged with grief.

“Twenty years they’d been wed,” little Sally’s uncle told Maine in an undertone. “Mariah prayed for years, and tried all the old folk-charms, too, before they were finally blessed, and now ...” He shook his bowed head and rubbed at his reddened eyes.

Maine and Sheer boarded the train back to London, leaving the locals dragging the stream. Maine read the paper, searching for clues.

“Slave trade in all its vile forms persists even now, at the dawn of the twentieth century,” he reminded Sheer grimly, and needlessly. “The reasons for which a child might be taken are numerous, but why from such a rural inconvenience, and by what means so craftily?”

“If it is slavers, do you think you will find them in the advertisements?” Sheer inquired. Maine had solved a kidnapping ring in this manner several years prior, decoding an exchange of notices by which the victims were sold to their degenerate purchasers.

“If they are using the paper, the code won’t be the same. But I must make the effort, as we have no better leads.”

That night, after a late supper, Maine engrossed himself in another newspaper. Sheer, who claimed no facility for codes, announced that he was taking a stroll. Maine nodded without glancing up. As soon as the door had thumped closed behind his friend, he cast the paper aside and followed.

Sheer walked down the street, turned into an alley, and then another even narrower alley. It was almost pitch black, and Maine stepped carefully, for fear of knocking some bit of debris with his foot and making a noise.

The alley ended at a dense park which Maine had never seen before. That such an unknown feature could exist mere minutes from his home was so beyond belief that Maine stopped short. But, seeing Sheer disappearing into the trees, he quickly took up the pursuit once more.

Under the trees it was almost as dark as the alley, just enough light filtering down to make solid objects a shade darker than the surrounding night. Sheer paused before a blocky shape that Maine guessed to be a stone monument.

After a few minutes, Maine heard the murmur of a low voices. Had someone joined Sheer without Maine noticing, or had they already been there? He heard Sheer reply, too softly for Maine to make out the words. Then the higher voice of a child.