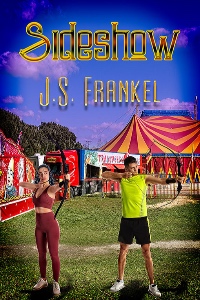

Irving (Irv) Isserlis, seventeen, is a sideshow archer, working for a small circus outfit based in the state of Washington. Irv is good, not great, but his partner and girlfriend, Artemis (Arty) McBain, can do no wrong.

She never misses, and one night, Irv finds out why. Arty—and another sideshow act, Hercules—really are the gods and demi-gods of myth.

A war is brewing. Pandora, along with Medusa, Ixion, and the Harpies, all villains from the ancient Greek myths, have come to Earth to steal the souls of the other gods who are hiding out there and protecting humanity.

Irv discovers that the stealing of souls is part of a larger plan. An unknown god is trying to foment a rebellion and claim power for himself, but only if he collects enough souls to challenge Zeus and Hera. If war comes, then it will be a war that Irv cannot fight by conventional means.

Yet, he chooses to join Arty, Hercules, Iris, and other gods and goddesses who are on the side of justice to fight against their mysterious foe. And it is only when the chips are down that Irv is forced to make the trick shot of his life.

Armand’s Traveling Troupe Of Unusual Acts. Spokane, Washington. June seventeenth. Ten PM. A packed crowd in attendance.

“Show’s over, folks. Show’s over,” the ringmaster intoned into a mic. “Thanks for coming, and give it up for Artemis and Irv, our resident arrows!”

Inside the big top, the crowd roared its approval, although it seemed as though Artemis got most of the applause. Of course, she got the most applause, and why shouldn’t she?

A statuesque brunette who matched my height of five-ten, with a figure that Hollywood would pay a billion dollars per picture for, Artemis McBain was a virtuoso with a bow and arrow, and my latest girlfriend.

Oh, wait, she was my only girlfriend. Who was I kidding? I’d only been at this job about a year. We’d been dating for six months, and since then, it had been one stop after another, one packed audience after another, and it all centered on her.

She called her bow Khris, maybe after an old boyfriend.

She shot blindfolded on some of our stunts.

She hit dead center every single time.

She’d recently performed her signature act that she’d called the Odysseus, which consisted of shooting an arrow from a kneeling position through seventeen needles in a row that stood four feet high. Their apertures were just large enough to shoot an arrow through—to a target that was only four-by-four inches.

What got me was that her bow—which only she touched and everyone else was forbidden to handle—was a simple wooden affair with no sight and no counterbalance.

Mine was also made of wood. The latest ones were made of graphite with cams. They were beautiful creations of science, but I stuck with tradition. My Mark II was from the Eliminator line. Not the best, but it had never let me down.

Artemis and I used the same arrows—Telegraph models, the best of the bunch. Her form was impeccable, and her shooting, unmatchable. She also never used gloves or even an arm guard.

Yet, she never injured herself. At first, I wondered how she did it, and then I realized that she was one of those super athletes who could do everything well.

I’d tried doing the Odysseus, but only in practice, never in a show. I couldn’t get beyond the first three needles. Either my concentration wandered, or my hand or shoulder shook—I simply couldn’t do it, and it bothered the hell out of me.

At the exit, one fan, a short, chubby kid, tapped me on the shoulder. His parents, also short and chubby, stood next to him, wearing tentative smiles. “You were pretty good,” he said. “Can I have your autograph?”

He proffered a pen and paper, and I signed my stage name, Irv Arrow. My real last name was Isserlis. It was Ashkenazi, or so I’d heard, although I’d never been religious.

As for my first name, who’d name a kid Irving? My parents had certainly had a sense of humor—not. After handing the paper back, he said, “Oh, Mr. Arrow?”

Oh, crap, here it comes, a compliment followed by a putdown. “Yes?” I replied.

“Artemis rocks, and you missed three times.”

The little turd couldn’t have been more than eight, so I couldn’t rip him a new one, much as I wanted to. It was against carnival law. “Twice. Hope you enjoyed the show.”

Off I went, leaving him to his parents. His parting shot followed me out. “She’s better than you and anyone!”

Brat—his parents had to be so proud of him.

The warm night air caressed me as I trudged back to my trailer that lay at the end of the fairgrounds. Along the way, I met a few of the main acts. They were part of the circus we worked with this gig—Farham Brothers. We were the sideshow act, but they didn’t seem to care, and they waved hello.

They were nice enough, but that comment by that punk kid had hurt. Still, he was right. I needed to be consistent. I could poke fun about my failed attempts only so often before people got the idea that I wasn’t that great an archer.

At my trailer, Armand Gussier, the owner of our outfit, met me, and, as always, he wore a smile. Perhaps he sensed my disappointment, as he said in a too-bright voice, “Nice job, Irv. Rough start, but a strong finish. You’ll get ‘em tomorrow.”

A rough start. I’d missed twice, cracked a couple of jokes to cover up for my ineptitude, and then I nailed the target after running and jumping off a ramp. It was a seemingly impossible shot, but I’d made it, and the crowd ate it up.

Gussier was a middle-aged man with a ready smile on a round, lined face. The lines came from the stress of scheduling circus shows and trying to bring in money.

He already had money in Artemis, Hercules—another sideshow act—and Giselle, our fire-eater. They were the big money-makers for him. I came second to them.

And even though I ran a distant second, Gussier never gave up on me. A short, fat man who had a habit of lighting up a cigarette anywhere and everywhere, he must have had infinite patience with me and the other newbs.

After all, he’d come to see me at an archery contest at my high school in Olympia, Washington. I didn’t win. I placed third.

Yet, he’d seen something in me that no one else had. We’d talked afterwards, and then he’d signed the waiver form as my guardian because my father—a person in name only—was too drunk to think properly.

Dear ol’ Dad had accepted the terms, but once he’d sobered up, his parting words were less than kind. “You’ve been a pain and a burden ever since your mother died.”