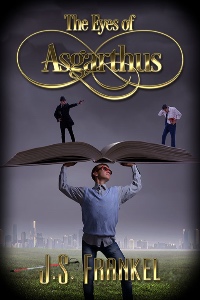

Asgarthus (Az) Anderson, Portland teen, is slowly going blind and there is nothing he or medical science can do to stop it. While he tries to deal with his impending loss of sight, he finds out that he has developed another ability—that of a form of psychometry.

In Az’s case, he can see people and events in objects that have been touched by strangers, but only the most recent happenings. His ability amazes and frightens him, and at first, he doesn’t know how to deal with it.

His girlfriend, Lynn Wong, is also frightened, but she stands by him as he tries to work through his newfound condition. Things change when the local police as well as the FBI find out about his abilities, and soon, Az is working as a profiler of sorts for them, hunting down criminals.

However, another case surfaces, one that baffles Az as well as everyone else. A killer is loose. The authorities have dubbed him the Silent Killer, as he creeps and kills silently and leaves no traces.

For some reason, Az can’t get a fix on him, and he doesn’t know why. The killer, though, knows more about Az than is thought possible, and now, Az and Lynn must do everything in their power to avoid becoming his next victims.

Portland High School, three-thirty PM, the last day of school. June first. Present day.

From what I could make out, the student body swirled around me, but I remained steadfast, a rock in the middle of rippling waves of humanity. Wait, that was a cliché, and the thought of it made me laugh internally. Cheesy line or not, that was how my life had to be—continuity in the form of chaos. There could be no other way.

Oh, God, that was a cliché, too. Fine, go with it. Life was a series of clichés. If a person was a writer, they’d twist the clichés around to suit their purpose. As a non-writer, I had to twist my own life around in order to suit me.

Snatches of conversation from the student body came my way, talk about summer vacation, where they’d go, and what they’d do—the usual stuff. Say goodbye to junior year and say hello to senior year in September. In between, they had parties to go to, swim dates, shopping and malling with their friends…they had it easy. I didn’t. Not that I couldn’t walk or anything. Being ambulatory was the easy part.

Seeing was not. My eyes had been rapidly and inexorably giving out for the past three months due to something similar to Stargardt’s Disease—that was the medical term the experts found to describe my condition, even though they didn’t really know what it was or how to treat it. Stargardt’s was the best they could come up with.

It sounded like science-fiction, and when the doctor pronounced the name, it made me wonder if I was really from this planet. Perhaps I’d been an interstellar orphan and had landed here by accident, raised by a kindly couple, and would become…

Oh, wait, forget that scenario. The sad fact was that I’d been born here, and the sadder fact was that due to this disease, I’d eventually lose most of my sight, if not all of it. And while the name—Stargardt’s—sounded sort of cool, the end result was anything but.

In simple terms, Stargardt’s meant that there was a disorder of the retina, the part of the eyes that sensed light and sent signals to the brain to process images.

“There’s a chance you won’t become completely blind,” the specialist said. His name was Ridpathe, an obese doctor who sweated with every breath as though he’d been forced to hike through the Sahara Desert at high noon.

“I can’t make any promises. But you will be legally blind. Your vision might end up as twenty-two-hundred. Maybe worse.”

How much worse could twenty-two-hundred get? Rhetorical—it couldn’t. Doctor Ridpathe told me another name for my condition—Stargardt Macular Dystrophy. “That’s the closest I can come to figuring out what’s wrong with you,” he’d said.

Screw the terminology he used or how simplistic he made it sound. No matter how he worded it, my condition would never improve. The world was growing blurrier and darker, and there was nothing modern science could do to stop it.

“For now, use a magnifying glass and enlarge the font on your computer,” the expert said. “If that fails, better learn braille. That’s the only way to do it.”

Harsh, that was beyond harsh, and my mother gasped before breaking down in tears. In spite of my shock at having my eyesight’s death sentence read out, reason crept in. Ridpathe wasn’t being mean. He simply couldn’t get involved emotionally. All he could do was lay out the facts. After that, Mother Nature would take care of the rest.

Me—I was too numb to respond, so when my mother recovered, she asked, “How long?”

Ridpathe consulted the computer and then turned to us. “There’s really no way to know, Mrs. Anderson. This is a progressive disease. I’ll schedule another examination next month.”

And, with that, the consultation was over. He might as well have condemned me to death. Not being able to see sucked. Before this happened, I’d been perfectly normal. Before—a six-letter word meaning normal, which was another six-letter word.

Crap. All the things I’d gotten used to as a sighted person, all the things I’d taken for granted, such as seeing colors, faces, and objects, all those things slowly receded into darkness.

“At least you can remember what colors are and the geometry of objects,” another blind kid I’d met once told me. He’d been blind from birth, so he had to go on touch alone as well as verbal descriptions.

Some consolation that was—not. I’d been a pretty decent archer before this happened. That was gone. Movies were gone, too. I had to rely on the soundtrack, as well as my memory of the images I’d seen before all of this happened.

Running wasn’t easy, either, as my depth perception and balance were off at first. I had to make adjustments. That meant walking, feeling my way around with my white cane, and remembering how many steps it would take to the bus stop, the classroom, and so forth.

Double crap. My life had been reduced to the sum of counting numbers. Now, it would take me thirty-seven steps to go out the main doors. I had a white cane but hated using it, so I slipped my left hand inside the strap and focused on my locker.

It stared at me, and I stared back. While that sounded weird, the tingle on my fingertips told me that someone had been here, and while I was trying to figure out who it was without making direct contact—direct contact triggered everything—I also wondered where my life was going and why I was still at school in the first place.