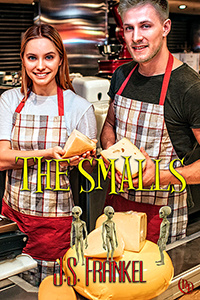

Greg Allenby, almost seventeen, is in line to inherit his family’s cheese-making business. He wants nothing to do with it. Bored with his life in Ames, Iowa, he thinks of nothing else except getting out of his hometown and going somewhere with his girlfriend, Jenny Gillis. Anywhere will do.

Everything changes with the arrival of three minute visitors. Artan and his wife, Kelindra, and her brother, Farkas, are from the planet of Chisaka, and they have nowhere else to go.

Greg allows them to stay, and they prove to be helpful with a number of skills they possess, but soon the secret is out and everyone wants to meet the little people, including the police and the armed forces.

Worse, the alien trio is being pursued by a malevolent individual from their home world, and now Greg and Jenny, along with the various lawmakers they meet, have to do everything they can to protect their new friends. But how you can protect yourself against something that you can’t even see?

June fifth, Ames, Iowa. Late afternoon. Second day of summer vacation.

People who worked with their hands were supposed to be the salt of the Earth, the common clay, the regular, down to earth human beings—in short, they were people you could trust.

“Those people are farmers, bakers, artists, plasterers, and common laborers. They know what it’s like to break a sweat. They do it day in and day out. They know the value of hard work. That’s what made this a great nation.”

A point in fact, those weren’t my words. That’s what my late father had once said. He was a cheesemaker. His father had been a cheesemaker, and his father had been a cheesemaker—and so on down the line.

And…where did that lead? It led to me, Gregory Warren Allenby the Fifth. It sounded high-class to others. Maybe so, but in reality, we were barely getting by. Names with titles meant nothing unless a person had the coin to back up that long-winded title.

What meant even less was that I was the fifth person in line to assume the mantle of taking over Allenby Cheeses, a small but well-respected business that had been operating in Ames, Iowa, for over a hundred and fifty years.

If I had been a dairy farmer—and we knew a lot of them, for what was cheese made from, anyway—then I would have said moo.

Since our factory made cheese, the word we should have chosen was squeak. Moo, squeak, did it really matter? I wanted to use a four-letter word, but my late father once said that swearing was the avenue of the ignorant, and maybe he was right.

Whatever. I had nothing against anyone who worked with their hands.

I had a lot against the idea of using my hands to fashion cheese. Forget about the machines that processed it. It still had to be made the old-fashioned way my ancestors at their primitive creamery had done it—by hand.

They did it by stirring vats of milk, by watching the temperatures in processing it, and by holding their noses against the rising stink.

Judith and Albert were our cheesemakers, and they’d been doing this job since before I was born. It may have been the only thing they knew, but they happened to be better at it than anyone else. I’d learned a lot about the art from them but could never match their expertise.

Judith came from a cheese-making family in her native Italy. Albert’s father had been a cheesemaker as well. It was a given that they knew their craft, and while neither of them possessed a college degree, hell, making cheese didn’t need one.

They had something better than a degree. They had wisdom and on-the-job experience. That made them gods, at least in terms of cheese-making.

It was because of their expertise that made Allenby Cheeses special, or so everyone said. That was what gave it its distinctive taste and “otherworldly aroma” as one critic from Des Moines once put it.

Reviews like these brought in some business. If I were a mouse, I would also have been in heaven. All the cheese one could eat and never worry about searching for another meal.

I was not a mouse.

Confession time—I’d never cared for the cheese-making side of life. My mother knew, my friends at school knew, and if I’d ever bitched about it on the internet, then the entire city of Ames and then the state and then the world would have known about it.

They simply wouldn’t have cared, though.

So, my dilemma was simple and yet complex. I didn’t want to continue the business. I didn’t like working the cash register or delivering cheese to the customers and restaurants on the weekends.

I also didn’t like it when the customers tried to bargain me down, and I didn’t want to be tied to Gouda or Brie or Jack cheddar for the rest of my life.

Anyway, what I did was part-time. My mother ran the business, paid Albert and Judith, and paid the suppliers and the repairman when one of the machines inevitably broke down.

Guess who cleaned up the place, though? Yours truly, most of the time and the smell was enough to make me gag. Wearing a gas mask should have been mandatory, but, apparently, my nose was hyper-sensitive.

Since my mother had requested me to do it—that was a nice way of saying ordered—I had no choice in the matter. “It cuts down on costs,” she often said.

When I’d gone into her store the previous Saturday to deliver some cheese wheels to customers, my mother stopped me just as I was loading up my bicycle’s basket.

“You don’t look very happy, Greg,” she said after she called me into her office. A tiny place, it was crammed full of files, documents, a few books, and her desk and computer. It only had enough extra space for a chair. A broom closet would have been bigger.

I’d just finished cleaning the factory, which lay about thirty minutes away by bike. The smell of Gouda lingered in my nostrils. It was a curse having an extra-sensitive nose. It took no longer than a millisecond to discern the different brands of cheese.

Still, that couldn’t be classified as having a superpower or even a special ability, and it certainly didn’t make me feel special. “What gave it away, Mom?”