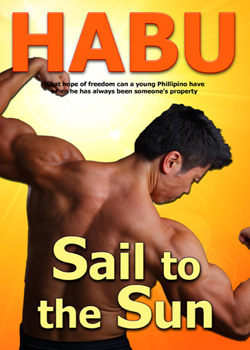

This is the saga of Atid’s escape from sexual servitude into the freedom to choose who, when, and how he will give his soul and body.

Young, mixed-race Thai man, Atid, could be transported by the brutal airman, Hoagie, from a shack near a U.S. air base in the jungles of Thailand, where he began servicing U.S. servicemen as soon as he came of age, to a swanky country inn in West Virginia, but he was no less owned by men who wanted to use him in America than he had been in Southeast Asia.

Hoagie, just the last of a string of men paying to own Atid, uses him as a waiter upstairs in his West Virginia inn and abuses him as a dancer downstairs in his gay bar and brothel. When the price is right, Hoagie sells Atid to a porn movie producer, who takes him to his mountain home and studio. Only rarely has a man treated Atid as anything but a possession. Buddy, the last of these men, Atid thinks has also used him and deserted him in his slavery, leaving Atid totally resigned to his lot.

This is a relaunch of the eXcessica novella by the same title.

“Shoot the moon.” Another voice sailing through the air—making my thoughts drift back, as the music drummed ever louder in my ears. I raised a slender, flexible leg high up the pole to cat calls from the murk, knowing I was nearing the moment when I unsnapped the thong and turned full frontal to the ring of reaching arms for an instant, a mere instant, before the spot was extinguished and I glided off stage, into the wings. There I perhaps would fall into the arms of a patron who had met Hoagie’s price—not knowing until Hoagie met us at the cell door what the price would buy.

Shoot the moon. Bringing to mind what my mother would whisper to me as she pulled the curtain across the bed, the smell of the smoke and the heavy breathing the man—invariably an American from the air base—having already told me the curtain would be pulled. Just another lonely and horny American airmen—just like the one of many possibilities who had fathered me.

“Shush now, little Atid,” she’d murmur. “Mother sails to the sun now.”

Each time she’d say that I would feel warm and close to her, as my name, Atid, meant “sun,” and for a moment, a moment only, I thought she was coming to me, to cover me with her arms and rock me back and forth and hum a tune of safety to me. But she never meant she was coming to me. And I would lay there on the other side of the thin curtain, hearing everything, knowing the moment she reached the sun, knowing she was being seared by the heat of the sun, crying out at the explosion.

It was not long, there in Udon Thani, before the American airmen came not always for my mother, but sometimes for me, and I learned myself what sailing to the sun could mean. Until then, I denied what it really meant. Sailing to the sun for me was rising out of the Thai jungles, above the trees and the fetid squalor of our alley and into the clean sunshine and the crisp air of the mountaintops. It was only a dream then; I didn’t expect ever to do that. And when I did get glimpses of it, I was sorry that it only shed understanding on the conditions I was born into. I think I would have been happier never to have known more or better.