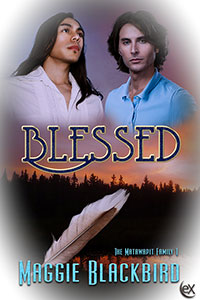

Bridget Matawapit is an Indigenous activist, daughter of a Catholic deacon, and foster mother to Kyle, the son of an Ojibway father—the ex-fiancé she kicked to the curb after he chose alcohol over her love. With Adam out on parole and back in Thunder Bay, she is determined to stop him from obtaining custody of Kyle.

Adam Guimond is a recovering alcoholic and ex-gangbanger newly paroled. Through counseling, reconnecting with his Ojibway culture and twelve-step meetings while in prison, Adam now understands he’s worthy of the love that frightened him enough to pick up the bottle he’d previously corked. He can’t escape the damage he caused so many others, but he longs to rise like a true warrior in the pursuit of forgiveness and a second chance. There’s nothing he isn’t willing to do to win back his son—and Bridget.

When an old cell mate’s daughter dies under mysterious circumstances in foster care, Adam begs Bridget to help him uncover the truth. Bound to the plight of the Indigenous children in care, Bridget agrees. But putting herself in contact with Adam threatens to resurrect her long-buried feelings for him, and even worse, she risks losing care of Kyle, by falling for a man who might destroy her faith in love completely this time.

Lying was what Adam did best. He’d learned how to lie as a punk-ass kid. Believing the lie for the complete truth was key in confusing the cops, the Crown attorney, the judge—anyone trained to search his face, voice, or body language for signs of dishonesty. Only booze had tripped him up, nailed him good enough to send him down below because of his love for the bottle.

He wouldn’t lie today. He hadn’t lied during his parole hearing, either. Lying wasn’t a part of his new life. Neither was whiskey.

From now on, fatherhood was what he’d do best.

Other parents sat in the waiting room at Children and Family Services. One paced the floor wearing yesterday’s stubble. Another shifted in her seat, bleary-eyed, either from a hangover or crying. The tall guy with holes in his clothes crossed and uncrossed his legs. The girl, not much older than twenty, rocked back and forth, slurping coffee, while her legs twitched. A tweaker, probably.

The smell was the same in all government buildings. A lingering of something old and outdated, and the walls either a bland beige, faded white, or dull light gray. Off-white was the color of choice at Children and Family Services.

“Mr. Guimond?” The receptionist rose from behind the rounded counter against the wall. “Your caseworker’s ready to see you. Second floor. The fourth office on your right.” She used a pen to point in the direction of the elevator.

Adam stood. His feet remained rooted to the floor, and he forced his legs to make the ten-yard trek to the elevator. Once he was enclosed inside the stuffy chute no bigger than the drunk tank he’d been tossed in after coming off a bender, he fumbled for the second-floor button.

There was no turning back. He was going up.

He could face a judge sentencing him, cops tossing him on the hood of a cruiser to handcuff him, scouting his range for the first time while being sized up by the toughest of toughs, or a beat-out from the Winnipeg Warriors to drop his colors. He could face anything but a caseworker who’d decide if and when he’d see his boy.

He checked his reflection in the mirror, smoothing his hair that kinked this way and waved that way. Damned wind was to blame after his walk to and from the bus stop. Since t-shirts, jeans, and running shoes wouldn’t impress the caseworker, he’d borrowed a too-snug dress shirt and dress pants off a guy at the halfway house. The buttoned cuffs were silver bracelets locked around his wrists, and the starched collar a noose.

The doors opened. His breathing mirrored the rattle and hops when he’d been chased by the cops. The same for the hot pressure pounding at the back of his neck.

There were offices in both directions. Some doors were open, a couple of them closed. Voices carried out from the offices, workers either on the phone or meeting with a loser like himself.

He gave his left a try first and trudged down the hallway. The fourth door on the right was closed.

Show time. He’d done this lots—getting his shit together before his execution. He fisted and un-fisted his fingers while huffing and puffing three quick breaths of air.

He rapped his knuckles against the fake wood.

“One moment, Mr. Guimond,” a woman said in a stern voice.

Adam’s heartbeat slowed, and the ball of tension behind his neck vanished. A few more seconds. He leaned on the wall and folded his arms. At least he’d gotten the right door. He’d also made sure not to smoke outside. First impressions counted, whether at a parole hearing, before a judge, anything. Smelling like an old cigarette butt was the wrong impression, but the blood threading through his veins could use a dart right now.

“You may enter.” The woman’s supposed invitation came out as an order. She must have worked at the iron house or had a husband as a CO.

He opened the door to a hawk—a birdlike biddy in her sixties with gray hair pulled off her narrow face and twisted into a bun. Beady cold eyes looked him up and down with the scrutiny of a judge on the bench. Her nose, the shape of a beak, she held high in the air. She pointed her skinny finger at the chair positioned in front of the desk, square in the middle.

“You may sit.” She lowered her hard gaze to a neat stack of papers and started writing.

Adam sat. The chair was positioned too close to the desk. Even when he opened his legs, his knees hit the cheap laminate. Maybe this was part of the caseworker’s strategy to make clients uncomfortable.

“I’m Mrs. Dale. Your son’s caseworker.” She kept writing on the pad, her scrawny knuckles a bright red from how hard she gripped the pen.

There wasn’t a smidgen of dust on the filing cabinet, desk, or bookshelf. One lone picture faced her. Pens kept in order of color sat in a tray. Even the essentials for an office were set square on the desk. There were no other files present but one manila folder which also sat square beside the paper she wrote on. The off-white vertical blinds were adjusted to keep the sunlight off her but allow the two blooming plants on a shelf to take in a tan.

With all this silence, she must want him to speak first. He swallowed a helping of saliva to keep his voice strong and calm. “I’m Adam Guimond. Kyle’s father.”

“I already know who you are and why you are here, Mr. Guimond.” The Hawk kept writing. “I have been responsible for your file since your incarceration.”

Double great. This old biddy had it out for him. Adam kept his arms unfolded. He stared at her rolled bun. He wouldn’t look anywhere else or shift in his chair.