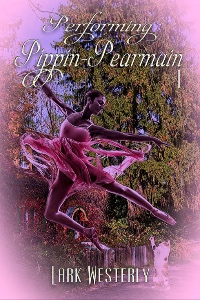

Eccentricity is Pippin Pearmain’s lifelong stock-in-trade. She used to be a niche-market performer, but at sixty-six, she hasn’t worked in a decade. That doesn’t matter to Pip. She has her cosy life at Lemonwood Cottage, an interesting friendship with Mister Clancy next door, walks on the beach and occasional stoushes with the officious and the annoying. She enjoys her regular ballet practice, and her daily battle with the bad-tempered lemon tree in the garden.

Pip has two cat companions, and if they choose to communicate with her in Cat-Morse about things no cat should be concerned with, well—no one else needs to know. Above all, she has her green-penned bucket list. That is unique.

An impulsive trip to her old hometown stirs memories for Pip when she meets her cousins Juniper and Lupin at the Delmsford Flower Show. Over a nostalgic afternoon tea provided by the Lilac Ladies in their retro-pinnies, Pip shares a long-held secret with her cousins and is given their secrets in return. Jan’s secret is fun. Lupin’s secret will be turning Pip’s life upside down…but not quite yet.

First, she has to negotiate the flower show… shuffle her place in the family pack and accept the unexpected gift of Lupin’s cat.

Pippin Pearmain had a bucket list.

It was a lovely list, recorded in green ink whenever she found a new bucket to add.

The list was her private treasure—something to occupy her mind during those queueing-around-the-block moments or green room marathons that stretched beyond infinity and back again. Not that there had been green room marathons lately—or even snaking queues, now she came to think of it. Jellico Bay, where Pip lived now, was deficient in both.

Still…she remembered how it had been.

Other people gossiped in the few short queues there were at the supermarket or at Jelly-and-Juice, or scrolled through their phones, sighed, and glanced at the clock, if there was one. Or they calculated the exact second when the parking meter, still manual in Jellico Bay though terribly outmoded elsewhere, might flick into an accusing triple zero with a decimal point to inform one it was an emergency but not a phone-dialable one if there wasn’t…a clock in sight, that was. Sometimes even Pip failed to untangle her inner syntax.

Who cared? Little Nanna Laurel had always said Pippin was one out of the box, and suggested they’d broken the mould when she was made. She didn’t mention whether that was a good thing or not. Little Nanna loved fiercely, and thoroughly, as she had done all things. The younger Pippin had wanted to be just like Little Nanna Laurel, but she knew she never would be. No one was.

Maybe that was why they got along so well.

Pip hummed happily in queues at a pitch that made some fellow queuers want to rub their ears and blame their tinnitus or a distant mosquito. They never blamed Pip, because she didn’t look like a hummer. She was so small and slender that she wore jeans in children’s sizes and little shoes that could barely hold coal at Christmas—if she’d ever been bad enough to deserve any.

People had never given Pip coal for Christmas. To her disappointment, they didn’t give her chocolate, either.

In the early days, directors wanted to keep her small, slight, and porcelain skinned. Therefore, their gifts to our little star were never chocolates, wine—well, of course not—or flowers. These were seen as inappropriate. Instead, they gave her charming seed pearl bracelets with enamel flower dangles. Mostly, the flowers were pink roses. Once, it was an orange marigold. The other regular gift was a high-end plush cat with a diamanté collar. She wore the bracelets to premieres, and sometimes the latest cat went too.

Tiny Pippin Pearmain attends the premiere of The Many Selves of Merry.

Much was made of the fact that she was technically too young to view the film, and so was taken out after the first half hour.

As Pippin grew into her later teens, the directors and casting agents apparently thought she stayed small by rigorous application of a sans-chocolate diet. No longer our little star but now that quirky ingénue, Pip continued to get the annual bracelets, now set with sapphires, garnets, or aquamarines. The plush cats were eventually discontinued in the early 1980s. Maybe someone noticed Tiny Pippin Pearmain must be nearing thirty. Maybe the cats went out of production. No one explained, and Pip didn’t ask.

Much later still, as that odd little woman—is she still acting? Really? she slipped off the directors’ Christmas list entirely.

Sorry, Ms Pearmain. The subtext was there, though it remained largely unspoken. You’re not suited to mumsy roles. You’re too small to be a love interest. You look odd in chorus lines. You don’t suggest Strong Heroine, Va-va-va-voom… First Victim, Third Alien, or Quirky Aunt, maybe.

It didn’t matter too much. Sully had warned her it would happen. And she was still acting, really, often enough to pay her modest bills. Not that she called it acting. If anyone asked her—these days few people did—Pip said she was a performer.

Pip’s waif-like dimensions were nothing to do with self-denial. She would always be small because her grandparents and her parents were all small people. If anyone had bothered to look up and apply the mathematical formula that allows one to calculate probabilities, then the result might have been quite close to Pip’s actual height in her little shoes.

Her cousins Lupin and Juniper had Big Nanna de Leon and Little Nanna Laurel for grannies.

Little Nanna Laurel was the granny they shared with Pip.

Pip had Little Nanna Laurel and Little Nanna Pearmain. Both ladies knew the value of wearing shoes that were practical while also tending to diminutive feet and pleasing the soul. They made sure Pip did, too.

Pip had nice feet, slender and high-arched with pretty toes.

Today’s shoes were green. They had yellow daisies on them.

Pip wasn’t being twee. The shoes were the only green ones she could find that fitted her perfectly. She planned to keep them for a long, long time. One of the advantages of staying the same size in perpetuity was the ability to wear clothing until it wore out. One of her favourite pairs of jeans had been purchased in 1979. They had the bell-bottomed silhouette to prove it.

Pip often dressed in green. When she was seven, she’d been a tree nymph in a naughty Greek play. She hadn’t had lines to say. All she had to do was to perch in a tree which had a handy ladder for added balance and peer down at the cavorting characters below.

Now and again, she tried to remember the exact title of the play. She knew she’d gone to lots of rehearsals, but she’d spent much of the time reading stories from her favourite book, which she’d propped in the crook of a branch, well out of camera-range. Grandmother’s Sunshine always absorbed her attention, but she could snap back to performance mode in less than half a second.