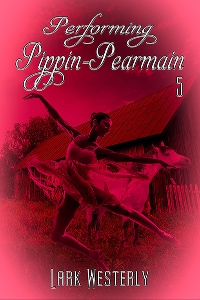

Fresh from her magical holiday at the fossmere and her first screen test in over a decade, Pippin Pearmain travels from Sydney to Delphinium Island to attend a dance festival and to appear in an indie film. From her arrival at the festival it’s all go, dancing to new tunes, meeting the other performers, and taking a chance to have her ballet, Delphine, workshopped with a real dance troupe. Filming the first scenes of Half-Life of the Lost is another challenge, as Pip has to perform unscripted.

While indulging in a bit of peace in a supposedly empty barn, Pip unexpectedly encounters someone she knew many years ago. Their connection dates from their shared love of the book Grandmother’s Sunshine, the mysterious family treasure that even the knowledgeable Jonquil from The Orange Grove bookshop believes does not exist. Pip has a new dilemma. Is a treasure shared a treasure diminished?

Pippin Pearmain slipped out of the guesthouse a full fifteen minutes before she and her agent, Magda Saxer, were due to leave for the festival at Delphinium Island.

Hoping to stay unobserved, she flitted along the short frontage of the terrace house and nipped round into the courtyard.

Lemon tree. Check. She paused to examine the shrub from a cautious distance. The one back at Lemonwood Cottage had savage tendencies and liked to collude with a sly-eyed gooseberry bush. This one looked cheery and gracious in comparison. Pip approached and stroked a glossy leaf.

“Hm,” she observed. “Edgar pees on you at the dead of night. Is that why you look contented?”

She moved on between narrow flower beds bright with late-season petunias and autumn crocus. Honesty raised its coin-shaped seed cases above the display. It was an odd mixture, but the colours harmonised.

A few more paces brought Pip within reach of her objective, a white-painted wooden gate. She’d used that gate this morning at around half-past-six. Edgar Treadwell, the kindly host of the guesthouse, had escorted her through and delivered her to her young friend Ardal who had stood back respectfully while she mounted Fimber the pony. Riding his own bay Indi, he’d taken her to Fosscot to enjoy her ballet practice with Jane.

Ballet in fairyland. What better way was there to start the day?

I must have been an excellent person in a past life to deserve all this. Or maybe I don’t deserve it, and someone loves me anyway.

Ardal had fetched her back in time to hand her into Edgar’s keeping.

“All reet then, lass?” Edgar spoke like a stage Yorkshireman, although he’d been born in Merimbula.

“Perfectly,” she’d assured him.

He’d taken her small hand in his large one and they’d stepped through the gate into the cool of an April Sydney morning.

Since then, she’d had breakfast with Magda and Edgar and his wife, Joan, and she’d readied herself for the next stage of her adventure. That would have less to do with riding and dancing and more to do with a return to stage and film for the first time in more than a decade.

I’m not scared.

There really was nothing to be scared of. For almost fifty years she’d been a performer who danced, observed, reacted, and spoke as directors required and scripts dictated. Performing had been kind to her. So had her acquisition of an intelligent and reassuring agent whose business decisions and financial acumen had steered her cosily through life.

So what if she’d not had a role in years? Her new agent had broken the drought. Performing was like riding a bike.

Pip backtracked a bit from that idea. She hadn’t ridden a bike in more years than she could remember.

Performing was like climbing a rope and squealing at a whistle-register pitch.

She’s done both of those the week before.

Pip put out her hand and brushed the wooden gate. It felt smoothly splinter-free, sturdy and faintly damp from the dew. She allowed her hand to glide over the uprights and onto the wooden latch.

You can do it. You’ve seen Edgar unfasten it.

She took hold of the latch and opened it easily.

If I step through into over there and it closes behind me…what if I can’t open it from the other side?

She smiled.

I’ll wait for someone, maybe Felicity Dark, to come by. Or I could go to the castle.

She pictured herself walking up to the arched wooden door of the castle, grasping the iron ring in both hands, lifting it, and letting it fall back against the door with a hollow boom.

What ho within!

Who goes there?

It’s me.

Who’s me?

Pippin Picotee Pearmain. I need someone to open the gate and let me back into Sydney.

It would be that easy. One of the courtfolk who lived there would greet her courteously and let her through.

Pip stepped through the gate and closed it behind her with a click.

To her disappointment, the castle was not in sight. Neither was the bridge, or the flat greensward where she had danced to Edgar’s mouth organ on her first Sydney morning.

She was in someone’s garden. Late tomatoes drooped on yellowed plants. A rake leaned on the fence, and an enormous cat glowered at her from his seat on an upturned stone urn. He was a monumental grey tabby with eyes the hue of green stained glass and a bi-coloured nose, striped in pink and black. That feature should probably have seemed cute, but it looked menacing instead, as if she’d caught the cat halfway through morphing from one colour to another.

There are things humans are not meant to see.

Pip liked cats. She lived with three of them and had lately met an interesting fourth called Patchwork Norah. This cat, though—

“Hello, Master Tom,” she said. He was clearly a tom.

The monstrous feline opened his mouth and yodelled at her.

“All right.” Pip made patting down motions in the air. “I beg your pardon.”

The intelligent eyes gave her a malevolent look. I beg your pardon, Sir. The voiceless words came to her clearly, full of contempt.

Pip stiffened her spine. So, the beast spoke Cat-Morse, just like her three feline friends at home. She said, “I’ll have you know I live with two of your sort. And another one who was touched by a guardian. And they’re all a good deal better-mannered than you are.”

Your point?

“My point is—” Pip paused. She knew more or less what her point was, but at that moment she became aware of a man standing silently not far from her left elbow.

He cleared his throat. “May I help you?”